On (Writing in) Hindi and Urdu

Over the last eight years, I’ve realized that one of the best decisions I made as a college freshman was taking Arabic. When I was studying at NYUAD, the beginning Arabic programs were focused on learning fusha, or Modern Standard Arabic. I quickly found myself very disillusioned – I was unable to have even the simplest conversations with Arabic speakers, as the gulf between their informal, spoken Arabic and my formal, written-but-spoken Arabic was often too large for me to grasp. However, I did learn the Arabic writing system. From the moment I could start reading words in Arabic, I was stumbling my way through the words written on signs in Abu Dhabi, the vast majority of which it seemed were simply transliterations of English words. To me this was the coolest thing in the world, especially when I found myself in contexts where there were no English equivalencies to help me out.

“Falaj Al Ain”, taken at the Al Ain Oasis sometime in late 2017

“Falaj Al Ain”, taken at the Al Ain Oasis sometime in late 2017

The tricky thing about the Arabic writing system, at least for someone experienced with the Latin alphabet in its English and Portuguese formulations is that fact that in all but learning or religious contexts, (short) vowel markers are omitted when writing. Take the word “کتاب”, or “kitaab”, which means “book” in Arabic (and Hindustani!) for example. When properly “vowelized”, this word appears as “کِتاب”; notice the little line under the first letter. Without this, we could just as easily pronounce “کتاب” as “kutaab”, or “kataab” – the reason we don’t is because we know that the little line under the “ک” is hidden. When I tell many English speakers about this, they wonder how anyone can read anything at all in Arabic. The answer is that when most people are reading texts in English, they’re not sounding out every word, rather they recognize words based on shape and context. That’s why you surprise yourself whenever you can read text where someone has removed all the vowels. (This whole discussion makes me wonder about rates of dyslexia in places where different writing systems are used, or in places where the writing system is used more or less phonetically. Spanish and Portuguese, for example, use the Latin alphabet in a far more phonetic way than English or French – there are few, if any, words like “Worchestershire”.)

After learning how to read and write in Arabic, I spent a year or so idly sounding out words like “باسکن روبنز” (Baskin Robbins) before going to Israel. In Israel, I was confronted with the language nerds wet dream – signs written in three writing systems (Latin, Hebrew, and Arabic). Moreover, just like back in the UAE, I found that two of the three languages were just transliterations of the third. Having heard that the Hebrew and Arabic writing systems were similar, I found that with some diligence, I was able to pretty reliably sound out Hebrew words. It turns out there is a one-to-one mapping between many letters in Hebrew and Arabic. This was pretty cool, but what truly blew my mind was the notion that there were groups of people who wrote Hebrew using the Arabic abjad and vice versa. In that moment, language became permanently decoupled from writing system. Sure, there are sounds that we create in English that can’t be represented by the standard Arabic abjad (take the sound English speakers associate with the letter “p”, the “voiceless bilabial stop” – this is not present in standard Arabic), but that’s nothing we can’t get around by adding on some extra dots or dashes (in Urdu, the “voiceless bilabial stop” is represented with the letter “پ”, not part of the variant of the Arabic writing system used for Arabic).

Last year in September or October I started learning Hindi. I have been wanting to learn Hindustani for a long time. From the moment I landed in Abu Dhabi and realized that a whole ton of people were conversant in Urdu, I wanted a piece of the action. In my head I use the words Hindi, Urdu, and Hindustani sort of interchangeably, so I’m going to do so here. Unless I specify otherwise, I’m talking about the spoken language understood in large swathes of Northern/Central India, Pakistan, and the Gulf. Socially and culturally, Urdu and Hindi are distinct, and in their written forms they are most definitely distinct – Hindi uses Devanagari, while Urdu uses a modified version of the Arabic abjad, generally written in the Nastaliq style. This spoken language, the one that serves a sort of lingua franca in parts of South Asia where tons of other languages are spoken (Gujarati, Marathi, and Punjabi, just to name three that come immediately to mind) is the one that I’ve been learning. As it is super convenient to be able to represent sounds on paper, I also went about the business of learning how to read and write in Devanagari.

Unlike the Latin alphabet, or the Arabic abjad, Devanagari is an abugida. Fun fact about the words “alphabet”, “abjad”, and “abugida” – “alphabet” comes from the first two letters of the Greek alphabet (alpha and beta), “abjad” comes from the first three letters of the Arabic abjad (“ج”, “ب”, “ا”) and abugida comes from four letters of the Ge’ez writing system, notably used to write Amharic (I don’t know enough about this script to write down those letter, apologies to all my Ethiopian audience members, although feel free to hit me up on Twitter). After spending so much time playing around with Arabic and even English, Devanagari was a breath of fresh air. Hindi, as written with Devanagari, is almost entirely phonetic, while it won’t tell you where to put the stress in a word, it will tell you exactly which phonemes are present in a word. There are two notable exceptions that comes to mind: “वह”, commonly spoken as “vo” instead of “vaha” as written and “यह”, commonly spoken as “ye” instead of “yaha” as indicated. Saying “vo” instead of “vaha” is so common that some publications, notably BBC Hindi, write “वो” instead of “वह”, much to the consternation of some of my Hindi teachers.

Over the course of the better part of a year (including some four months of intensive Hindi lessons) I have gotten reasonably proficient at reading Devanagari, to the point where I can read some words on sight instead of having to sound them out. I can take notes in Hindi almost as fast as in English, despite my contention that the script is very “verbose”, as in it takes many strokes to draw letters. That said, I’ve seen some shopkeepers in India and the UAE write Devanagari in a manner that puts my mom’s cursive to shame.

Very recently, I’ve started learning Urdu more formally; in addition to learning more Urdu specific vocabulary and phrases I’ve been reading and writing in the Urdu variant of the Arabic script. In printed form, a lot of Urdu uses the Nastaliq calligraphic style, which while very beautiful, is daunting to someone used to the Naskh style found in the Gulf.

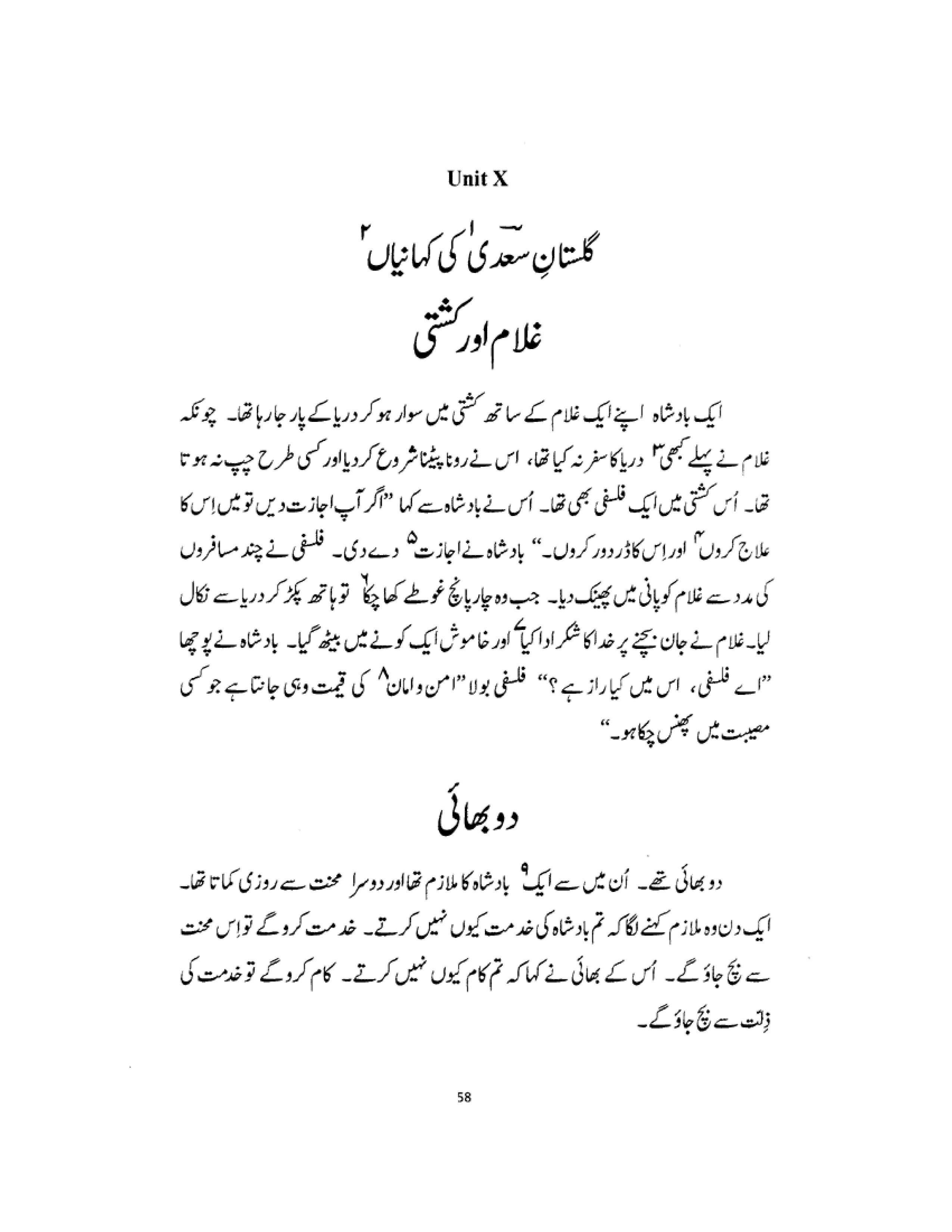

An example of the printed Nastaliq style. Taken from here.

An example of the printed Nastaliq style. Taken from here.

Recently, however, as I stumble my way through stories designed for children (shout out to Habib ji for his unending patience) I find that something wonderful is happening: the sounds I’m reproducing, as prompted by the squiggles on the page in front of me have meaning. In the past, whenever I’ve read Arabic texts, its just a series of unrelated sounds that have no meaning to me, as I don’t speak Arabic. Now, when I read Urdu aloud, fully formed words, with meanings and histories and cultural contexts tumble from my lips. To me, this is completely magical.

As an 18 year old, I started learning Arabic, and for a variety of reasons put it on hold. These days when I read Urdu, it feels like I’m finally continuing that journey I started eight years ago, albeit along a very different path.